From Seed Round to Series A in Ontario

As a sometimes-founder, sometimes-angel, I have always wondered about funding and finding a source of information as a benchmark. “Are we taking too long to do this thing?” “When should we have started to do that thing?” “Do I need to talk about this at that meeting?” “Am I missing this in my plan?”

One question I asked and one that was asked regularly by teams I visited as an angel was “How long after a Seed Round should a company get a Series A?” Three companies ago, I went to my lead investor for advice. But to my surprise when I blurted this out over coffee he basically looked back at me and said, “You should know!” He was absolutely right. I should. But what I wanted was an answer to another question, “if I want $X million in the bank by date Y, when do I have to start the roadshow? What is a typical roadshow? How long do they take?” Fundraising was hit or miss for me. It was hard sitting across from a person 25 years my junior as they explained to me what the Internet is or what a cell phone is. I have tried to be so successful, I would never have to deal with such clueless punks again, and now I want to convey a bit of what I learned so you all can be more successful.

The Deal Flow

We went through our public deal flow database we have at theMIN.ca and started some research. We started off with companies that have headquarters in Ontario. Companies that published the Seed Round attributes such as amount, date, investor. Companies that published the same amount of information about their Series A if it occurred. Finally, we tried our best to track whether a company was active or not. Basically, this was the following: check that the website works, that LinkedIn has people currently employed there, Dun & Bradstreet may have a file on them, and Industry Canada has a listing for them. Our database has companies from summer of 2000 onward, so about 18 years worth of data. We don’t see all deal flow, but the major VCs, Angels, and Wealth Funds who publicize investment and acquisition to stay transparent.

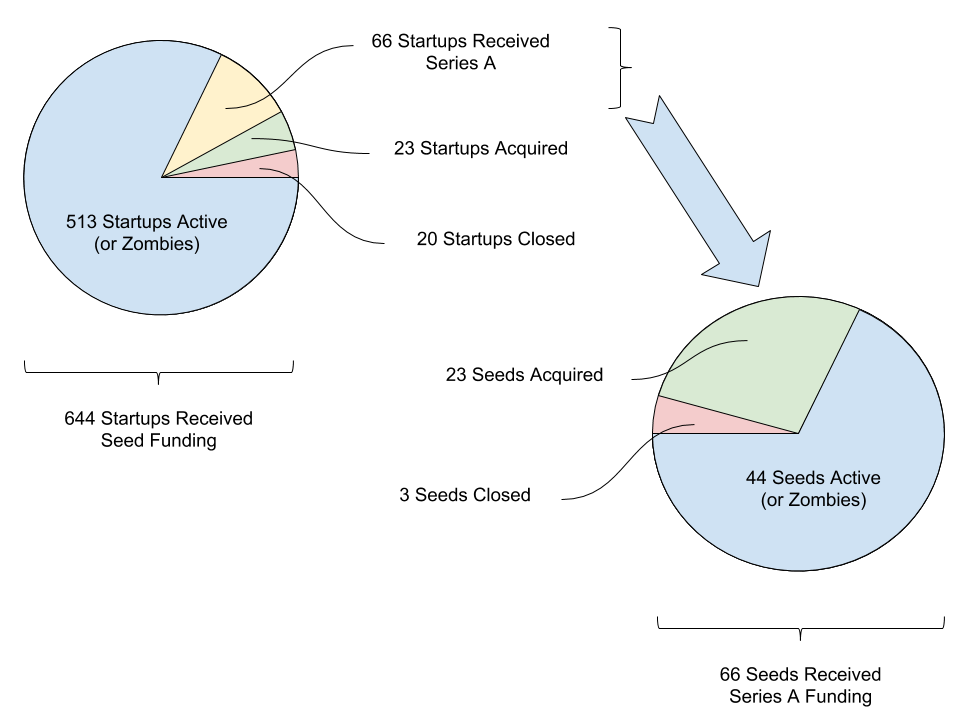

We found that 644 companies fit our filter. Another 899 did not report the amount of their seed round. An astounding 547 are still active of the 644 in the primary group (this may be more for our selective data inputting in the past than reality). Only about 10% of these companies received a Series A. We don’t have information about who tried for one and it wasn’t granted, so this is just a number in our books. But it does show you that a Series A is not always needed, guaranteed, or granted. Don’t go overboard quoting these numbers. Most startups fail after the 2nd year, and funded startups have a slightly better success rate. Our rates are for a selection and should be taken as truthful only for this publicly available information.

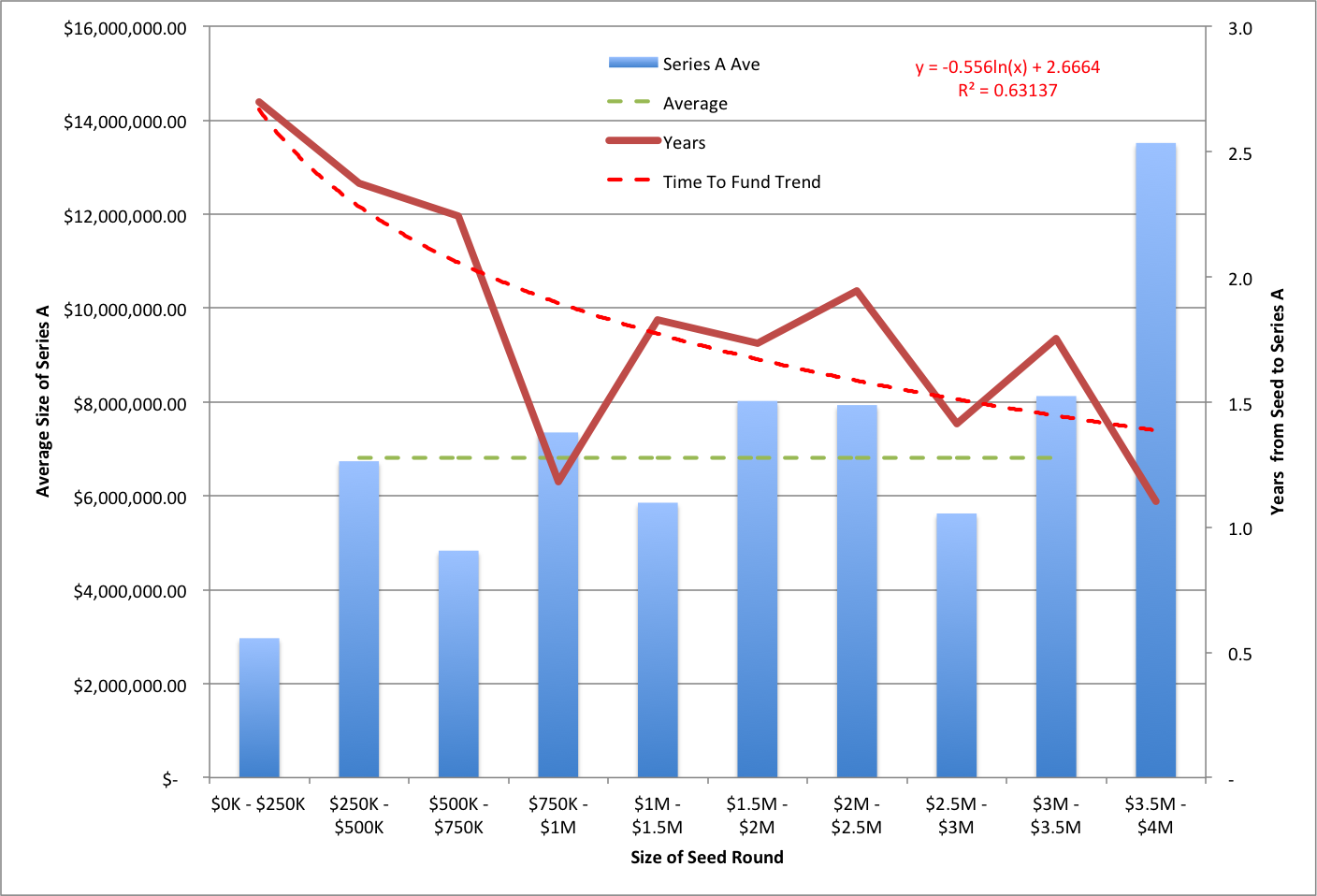

Next, we binned the 66 companies of the 644 who reported the amount of the two raises. To create the following graph.

The bin groups are in $250k-seed groups below $1M Seed Round and $500k-seed groups over $1M investment. The blue bars are the average Series A raise for that bin group. The solid red line is the average number of years for each bin group to get a Series A. You can discover what you like from the graph, but here’s what I get out of it. Firstly, a Series A in Ontario for companies getting a Seed of $250K-$3.5M is on average about $7M (green dotted line). Secondly, the time from a Seed Round to a Series A event drops from around 2.7 years for a $250K seeded company to about 1 year for a $4M Seed Round (red dotted line). There are a couple of questions that come to mind, how can a company spend 2 years living off of $250K? These companies might already have offsetting revenue and they took less money because they needed less. How can a company get $4M in a Seed Round and then have to go back to the markets for a Series A of $13M? I can see a funder liking the scaling possibilities and putting these amounts into the second round.

The bin groups are in $250k-seed groups below $1M Seed Round and $500k-seed groups over $1M investment. The blue bars are the average Series A raise for that bin group. The solid red line is the average number of years for each bin group to get a Series A. You can discover what you like from the graph, but here’s what I get out of it. Firstly, a Series A in Ontario for companies getting a Seed of $250K-$3.5M is on average about $7M (green dotted line). Secondly, the time from a Seed Round to a Series A event drops from around 2.7 years for a $250K seeded company to about 1 year for a $4M Seed Round (red dotted line). There are a couple of questions that come to mind, how can a company spend 2 years living off of $250K? These companies might already have offsetting revenue and they took less money because they needed less. How can a company get $4M in a Seed Round and then have to go back to the markets for a Series A of $13M? I can see a funder liking the scaling possibilities and putting these amounts into the second round.

Deal Timing

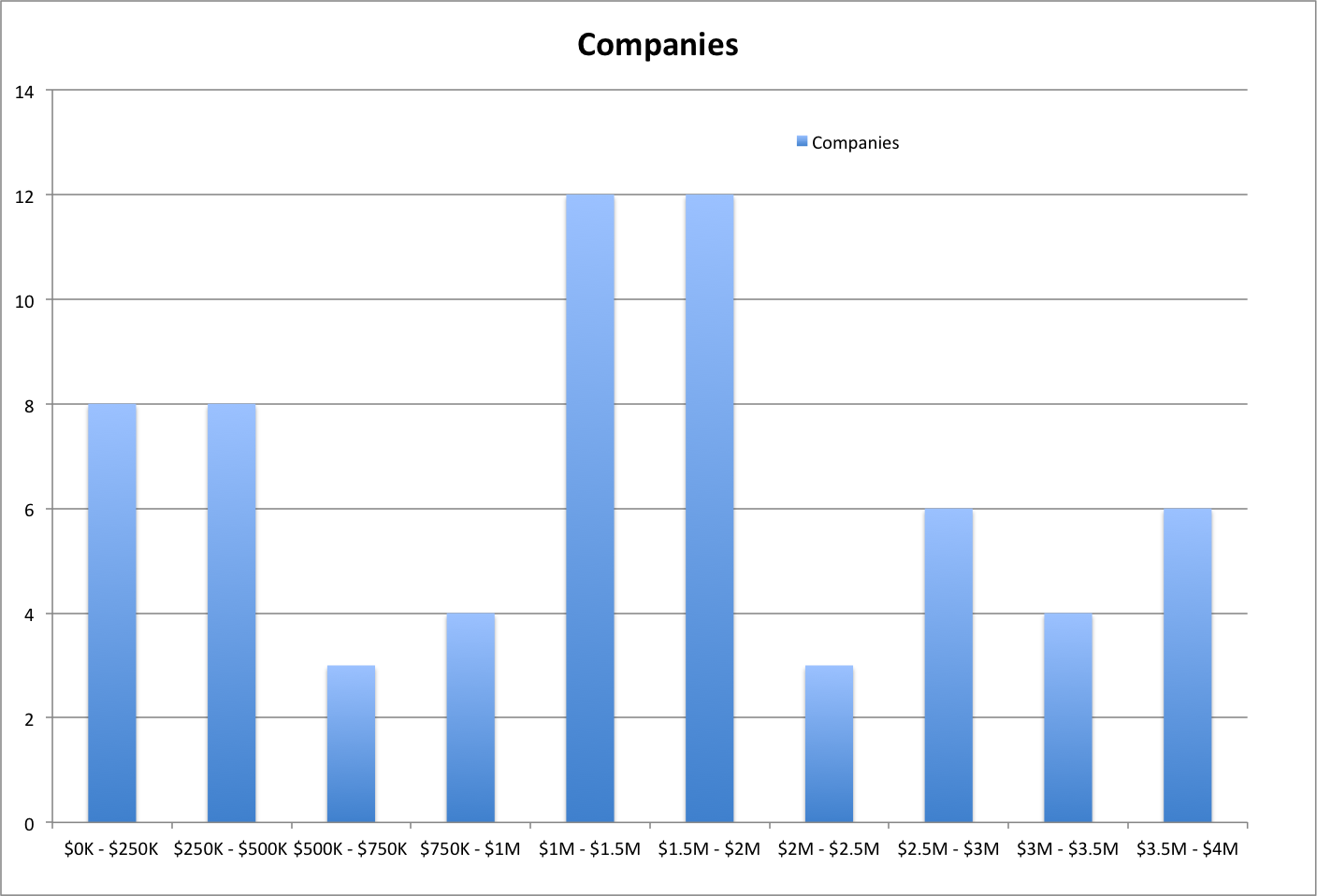

Here is a distribution of the companies that shows that 24 companies received seed funding in the $1M-$2M range, while 16 companies received under $500K. From my experience, it’s rare for a startup to ask for $550K or $950K. But $1M or $500K is seen often. There shouldn’t be this gap, but there is in this chart and in my experience.

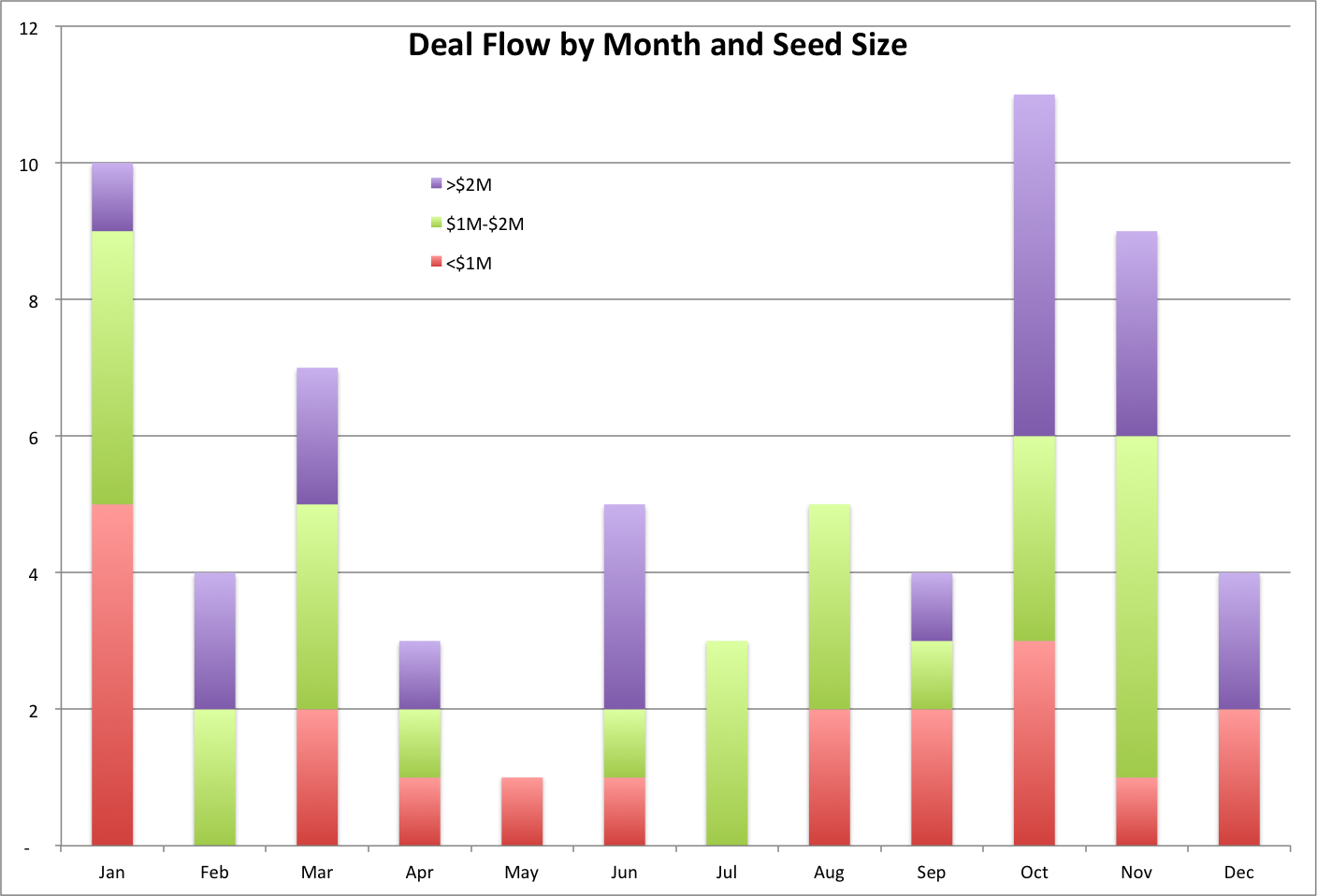

Another interesting thing is if there is a best time to ask for money – summer, fall, etc. From the table below and the expanded graph, we can see that deal flow was not equal across each month.

| Period | Deals |

| Q1 | 21 |

| Q2 | 9 |

| Q3 | 12 |

| Q4 | 24 |

This could be the timing of the company or this deal flow could be induced by the Investors. My guess is you should plan for these dates as the dates you get your money and work backward the 3-7 months of seeking money. So for October start seeking money in April, for January in July. If we break up when the deals were done based on the size of the Seed Round we see another graph.

Basically, the smaller-sized Seed companies (<$1M – red), raised their money throughout the year, mostly in January. The mid-sized Seed companies ($1M-$2M – green), raised their money in November and January. The large-sized Seed companies (>$2M – purple), raised their money in October with smaller deals in November and June and never in July and August. When we examined when deals were made by the top VCs, it was clear that deals where publicised rather evenly throughout the year. But when we looked at when companies Lead and when they Followed-on showed that most companies who Lead did fewer deals of that type during the Summer. My only guess here is the people doing the Due Diligence were off and the load had to be reduced. But they Followed-On evenly throughout the year. So I guess an LP or VC reviewed things quickly in the Summer when some other VC Lead.

We know when to go back to the market based on what my Seed Round is, and we know how much to ask for. Now, how long does the process take?

Road-Show Expectations

If you think this first part was unscientific, pull out the Ouija Board and the Tarot Cards, because this next part is a pure argument rather than empirical proof. We went to the major Series A funders and asked them for their checklist to consider a Series A and the time it takes to get the money. After a few quick emails and shared URLs, we discovered they had no time for us. So we went to the people who negotiated the Series A in our study for their input. Most of them had no time for us. But we did get some responses (exactly 10) and here are the results.

- 100% went back to their Seed Round funders for more money first

- 80% of Seed Round funders introduces them to follow-on funders who they have worked with before

- Only 10% of Seed Round Investors were involved in the Series A

- Bridge-debt and spot rounds of Angel Investments where suggested in 20% of the cases

- From 4-30 presentations where made for investors, the median was 12 presentation

- Most presentations were done by teleconference with the key presentation being done in person

- The process took from 3-12 months to complete

- Most agreed that they could have started the Series A roadshows sooner but they wanted good news to report on their decks so they waited for some key milestones to be reached

- Meetings were booked once they had good news, in one case they had no good news, but spun what they had – they all wanted to demonstrate that “lack of cash was a constraint”

- DD period usually took one dedicated person at the company about 15 days of collecting information and sending data per Investor signing an LOI

- Most have exclusivity requirements for a DD session so you couldn’t do two DD sessions at once

- Each group had between 1-2 DD periods in the fundraising cycle

- Much of the information collected for one DD period was reusable for the next

- No one went shopping for better terms after they received their first term sheet

- The Series A ranged from 75% to 110% subscribed

- All companies had positive Y/Y Revenue growth in the range of 50%-90%

- ARR of +$1Million was mentioned in 2 of the 10 case

Conclusions

Unscientifically (we didn’t call the companies who didn’t report a raise but maybe tried), you need to start fundraising and visiting your 12 investors about 7 months before you need the money from one of them. You might also want to consider the size of your Seed Round and decide when to fundraise based on when things seem to happen with these graphs.

One last piece of information is to expect rejection. These 66 companies in our dataset are survivor-biased. The actual numbers are 1 in 40 companies will get a Seed Round. 1 in 400 will get a Series A. Most people don’t want to know how the sausage is made, because the truth hurts. But I have the deepest amount of respect for the dreamers – so don’t give up. The answer will come from your hard work!

Executive Summary

- An average Series A is about $7Million for an Ontario-based start-up

- The average time to close a Series A ranges from 2.7 years for a small seeded company to 1.1 years for a larger seeded company

- A successful contact-to-funding for a Series A is in the range of 1-3 months

- Most Series-A-searches for an interested contact takes between 3-9 months

- 1 in 10 companies who are seeded have the operational results necessary for a Series A

- Larger seeds need to pass on Summer Funding activities (maybe because the larger funders are off in this period)